In Support of Dissent

"The culture of power-over people with developmental disabilities is stubborn. Admonitions to respect the right to choice and dignity of risk are seldom sufficient to relax its grip. The dominant presumption that something about a person demands fixing or treatment hijacks thoughtful consideration of a whole person’s purposes, will and preference and empowers professional judgments about health and safety. The struggle to create the conditions to intentionally exercise power-with people continually challenges our practice.”

Recently, seven of our colleagues in inclusion from across the U.S. (Carol Blessing, Marcie Brost, Beth Gallagher, Kirk Hinkleman, Peter Leidy, Beth Mount & John O’Brien) published DISSENT FROM CONSENSUS: A Response to the Person-Centered Planning & Practice Interim Report.

The Practice Interim Report in question is a piece developed by a consulting company commission by the US Department of Health & Human Services to come to a consensus on defining person-centered planning for systems.

Our colleagues write passionately about the danger in “consensus” from human service professional and government entities around a practice and experience that has given birth to a variety of dreams, imagination, clarifying identities, competencies, and giftedness, and emerged a vision of newness for people with developmental disabilities, their families, and our communities.

Starfire fully supports the Dissent opinion and rejects any effort to standardize, mechanize or otherwise systematize, a practice which has given life to numerous people with developmental disabilities, their families, and our communities.

Our colleagues’ writing reads to us, as a list of what people with disabilities and their families and the people who care about them are up against - in one concise and beautiful sentiment. They make a case for the wisdom and usefulness in “chaotic self-organizing” allowing people themselves to design, experiment, plan, and dream alongside the support from family members, service providers and community members to bring to life the possibilities set forth. It is, at the heart, what person-centered planning has been designed for.

Person-centered planning has had the most profound impact on Starfire’s work, radically shifting our understanding of our role in people’s lives and setting us in motion phase out of legacy and congregated models of group support.

Allowing people to come to get to dream, ideate, and set action steps together for what a good life can look like and can mean, they write, “person-centered planning as one disruptive element in a purposeful process of organizational and social change.”

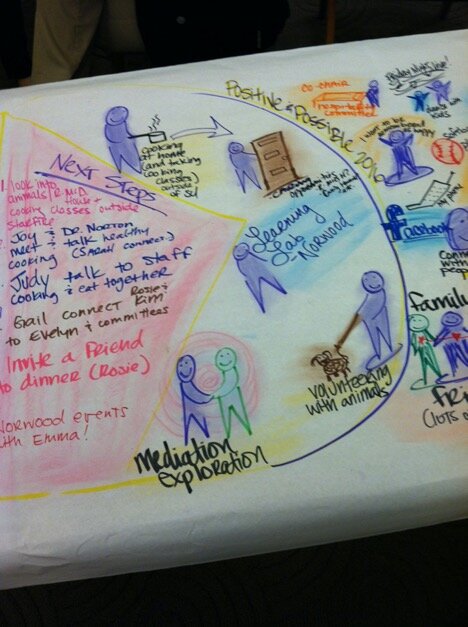

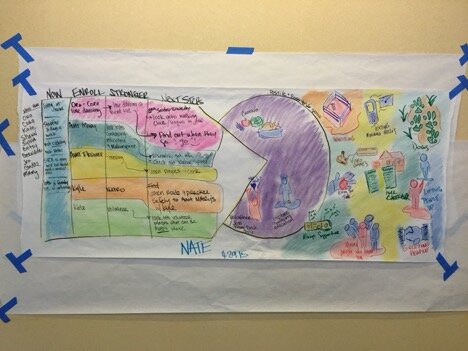

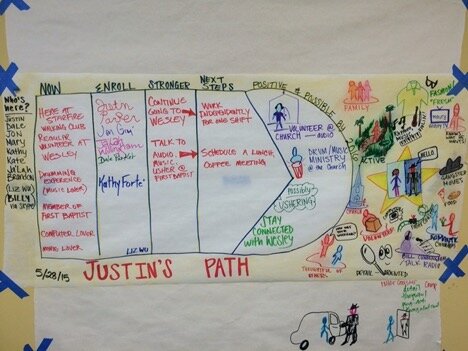

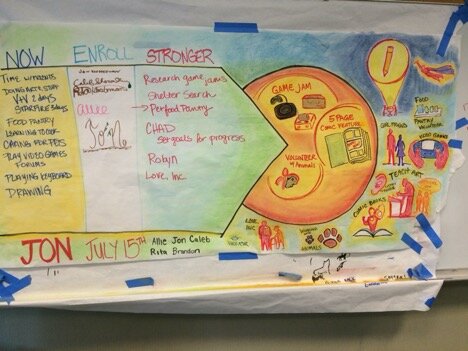

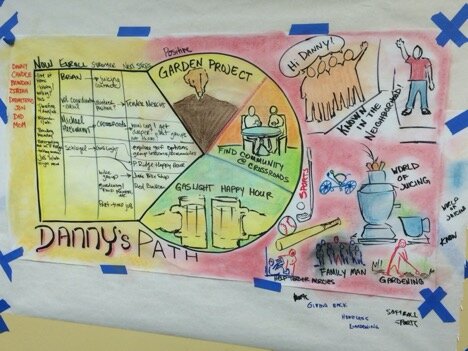

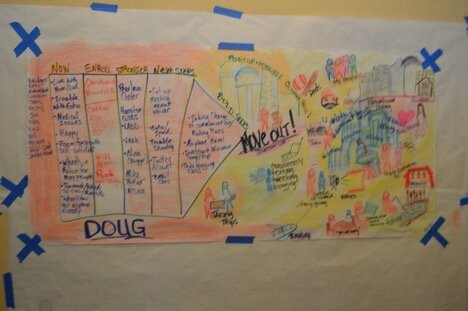

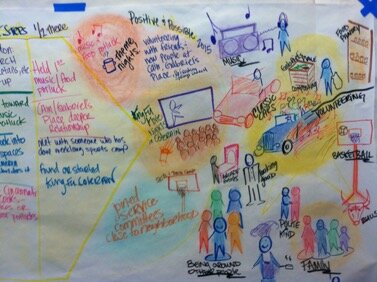

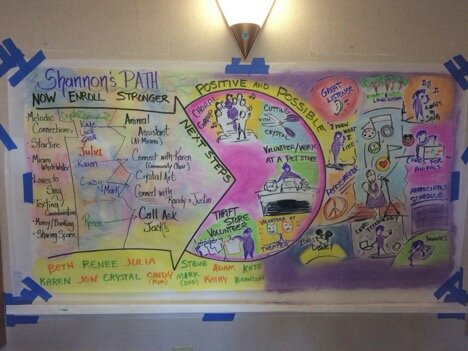

This has been my experience in 100+ person centered plans that I have graphically facilitated and helped to host since 2010, representing 100+ unique people, stories, their families, and their dreams of what an inclusive, good life could and might look like with a little luck and some good work.

Admittedly, there were suggestions made in the 100+ during person-centered plans over the past decade that I have been in that I simply didn’t record. Once, a suggestion that Beau would be happy in a nursing home (at age 23) because they had lots of activities and he could be kept busy. We were able to shift the conversation to what kind of business was important to Beau, and the conversation led to a dreaming around teaching kids to swim, volunteering at a local school and the idea of institutionalization fell to the wayside. Having something important to do was at the heart of the suggestion, and this uncomfortable pause with markers in hand, allowed the conversation space to breathe. And it stopped “nursing home” from being Beau’s North Star.

Another time, a debate about scheduled laundry days was a part of a vision for a good life for JP. We were able to navigate the conversation to what a good home life looked like to JP and steered the conversation into autonomy around his days with his group home staff, setting up a schedule that worked for him and wasn’t regimented on rotating staff schedules that conflicted with his love of WWE Monday night raw events.

The Consensus report lists competencies and qualities required of a good facilitator, and many of which Starfire would agree with. However, an exhaustive list wouldn’t cover the examples above – how to navigate a conversation back to the goodness and intentions of inclusion and assuming a facilitator holds the same values of inclusion. How to hold space and sit silently while a “bad” idea is proposed, how to assist the group to continue to remember the good things in life are not often found in services, strict schedules, congregated programs, disability-centric opportunities. While the competencies as a whole are a good list, it doesn’t encompass the intangible skills of allowing a conversation to flow and capturing the big idea, the good life idea, and sift through filler that is often not in the best interest of the focus person, not truly inclusive, and neither positive nor possible.

In 2010, Starfire began to fully invest in learning about person-centered planning, and about PATH planning specifically. As I’ve written before, I was admittedly, skeptical. The idea of putting down to paper a vision for the future seemed ludicrous. We practiced mini-PATHs for each other, and colleagues walked away hanging their posters above their cubicles. I recycled mine.

From Things Change and That’s the Way it Is Part 1:

“Bridget learned about PATHs, and lead a staff training on it to bring us along…We did very small personal mini-PATH’s (the North Star conversation only on speed.) I remember my North Star included buying a house, getting married, learning about bee keeping, starting a garden in my backyard, writing, and a few others that I can’t remember. I was skeptical about the whole process, not buying into the hippie shit of drawing what you’re feeling and dreaming out loud, and all the other hokey stuff I thought I’d left behind from when I planned retreats. At some point, I became embittered by it. We gathered as a large group again, shared our North Stars and at the end of the afternoon, everyone rolled theirs up and took it to their desk. “I’m going to keep this” someone said. “I’d love to hang this above my desk as a reminder of what I could be. I’m embarrassed and ashamed now to say that I felt very differently. I immediately crumpled it up and recycled it. The idea of “writing something down and seeing it as an image makes it more probable to happen” was bullshit. I was not an immediate believer in the process and wasn’t buying that this was something that would really change people’s lives. And who cares about drawing pictures? Was I ever going to really learn to keep bees? Buying a house? When I’d just graduated in 2007 with large amount of student loan debt and was paying out of pocket for graduate school?”

And yet, I did do all those things, which I later blogged about here, and here, and here. And many people whose PATHs I was a part of have also gone on to accomplish their goals, bring to life their North Stars, on their own timeliness outside the bounds of a service system which mandates outcome reports, yearly MyPlans, skills assessments, billable hours, and the like.

"When we think of person centered planning, we think of specific faces, names and stories. As we read it, the Interim Report aims to meet health system demands that position person centered planning as an instrument of that system, bounding a universally defined process in meetings, specifying competencies to facilitate plans, and outlining system management processes to assure compliance in implementation."

Likewise, when I think of person-centered planning, I think of 100+ PATHS. Conversations that were joyful, laughter filled remembering best moments, childhood stories, inside jokes and time spent in communion, tough and difficult (I want to move out/I want her to move out), conversations that led to new identities – docent, brewer, fashionistas.

Starfire will continue to incorporate person-centered planning into all that we do. Not because it’s regulated and or perhaps required, but because its role in our work continues to hold importance and power for people with disabilities, their families, and our communities. And because we’ve seen, what happens when we invest fully in what is positive and possible.