When I applied for my job at Starfire, we were at the tail end of forming our new Strategic Plan and Tim was in search of someone who could develop outcome measures during the organization’s impending transformation. Being that this was my first experience with any type of outcome collection, it worked in my favor that he wasn’t asking me to come with all the answers. Instead, he wanted me to take a back seat, so that eventually I might “draw out” measurements that would be both respectful of the people we serve, while honoring the impact we make. Leaning on my background in Anthropology, I started by interviewing key people, taking lots of ethnographic notes, and immersing myself in the patterns at play.

“…Someone who has an ability to listen, support and appreciate the stories we bring and draw out the measurements that may be hidden in the narrative side of our work.” -Tim Vogt, email to me in 2011

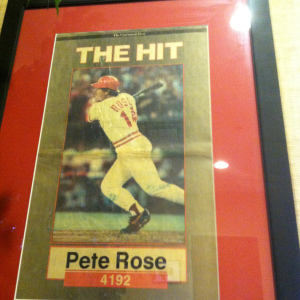

At that time, Starfire’s building was buzzing. Morning and night, it could be seen as the premier “hub” in the city for people with developmental disabilities to access social activities. At our height, we offered a calendar of 100 social outings per month for 500 people. Our vans could be seen around the city, driving groups of 10 or so people with developmental disabilities, along with a staff and a volunteer to events such as Red’s games, out to eat, or volunteering. Our day programs were at capacity, where during the week people would come to Starfire to learn “life skills” such as cooking or creative writing, or go on “day trips.”

We measured our impact using tools developed in partnership with a local university — as well as our own surveys. The Life Skills Assessment measured what “life skills” our members were capable of in order to make them more independent. Staff took hours to complete this assessment for each person. They poured over a list of over 200 skills and decided who was capable of what – from making the bed in the morning, to giving a proper handshake. With a list this extensive, there was admittedly quite a bit of guesswork involved. Some skills didn’t even seem relevant, like tying your own shoe (velcro, anyone?), or knowing where the nearest post office was (I can’t tell you the last time I mailed anything from my neighborhood USPS).

In addition, a survey by staff was completed after each outing activity. These forms assessed how much a staff thought a person “participated” in the activity –one of the questions being a checkbox yes/no for “eye contact.” Finally, a survey was sent to parents and caregivers each year that rated on a 5 point scale how well they agreed with statements pertaining to their son, daughter, or client’s social life.

“Starfire Member is less lonely or isolated because of his/her involvement with Starfire (circle one) 1 2 3 4 5”

Across the board, these assessments were done behind closed-doors, with staff cramming the assessments in a couple of weeks before they were reported on, or filling them out at the end of their shift in a hurry. Parents filled out their surveys at home and mailed them back to us, but little was communicated above and beyond the survey completion.

And in the end, our outcomes painted a pretty nice picture. Not only were we popular among families, but we were also kicking-ass at skill development. The numbers affirmed the work we were doing was impactful. No one was saying otherwise.

That was our story.

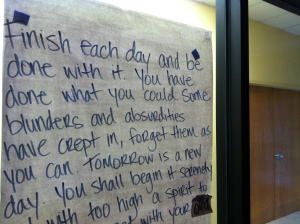

Before we realized the power of outcomes, it wasn’t clear to us how our 100% skill increases and 99% satisfaction rates from parents were getting us “stuck” in a mode of operation that wasn’t actually impacting people’s lives the way we hoped it was. As a result, our outcomes served the system, defending and propping up an outdated model of support for people with developmental disabilities. The unintended consequence of our “success” was that it masked, or at least completely missed, the real problem and issues at stake in the lives of people with developmental disabilities.

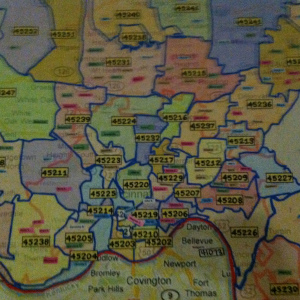

Statistics painted a picture for part of what was missing. People with developmental disabilities face an unemployment rate of 83%, a poverty rate 15% higher than those with no disabilities, and experience a rate of violent crime 3 times that of the general population. And while our organizational data wasn’t helpful in revealing these facts, our stories were. After 20 years of good work and “successful outcomes”… these “statistics” were people we knew well.

To be fair, at this point our data did teach us one thing: that what we were measuring was not congruent with meaningful impact. We knew people who were being prostituted, jailed, abused by caregivers, people who didn’t even attempt to join the workforce and who were chronically depressed, anxious, and stressed. The common denominator in all of these stories wasn’t that they weren’t participating in enough fun activities, or learning the right amount of skills, or even that they all live with disability. What spanned across all of these stories, then and now, is the sheer isolation that people with developmental disabilities face over a lifetime.

Starfire, being the “hub” that is was, worked to group all people with disabilities into one place – separate and set apart from the ordinary activities of community life. We had effectively created a proxy for what being in community might feel like, but without the true benefits that actually belonging in the community gives. We knew at that point that if we were going to change their condition of social isolation, then we had to stop sending the message that people with developmental disabilities belong “with their own kind,” or in special groups, separate from the rest of community. Instead, we had to re-design and innovate our model so that it would work first to open the hearts and minds of people in the community and begin to tell a different story than “disability”…

(p.s. here’s a helpful article from Harvard Family Research Project about slowing down to get to the right kind of evaluation…http://bit.ly/1Ma6eoN )